Click on images for better view

Front seat in a Chevrolet Blazer is a frighteningly up-close way to see India. My colleague, (Jaird de Raismes, the other laggard from the group, who also preferred to stay on at the incomparable Palace Hotel in Mt. Abu) and I preferred hotel-door-to-hotel-door service to the train. The trip from Mt. Abu to Pushkar took about seven hours. In the United States it would have taken far less, but driving in India is something entirely different. First of all, the roads are two-lane highways. One uses both sides of the road equally – actually maybe more time on the right (the oncoming traffic side), trying to pass. Every such passing maneuver is heralded by a horn blast. Each truck has Blow Horn Please painted gaily on its rear. Oncoming vehicles also blow their horns and flash their lights. After a bit, the jittery American passenger riding shotgun in this suicidal operation grows inured to the close shaves and chicken-run contests with over-loaded trucks. Everyone knows the rules and pays close attention, so foreign sensibilities to the contrary, it’s all quite safe.

Indian roads have very serious speed bumps, though, high and sharp, which require all vehicles to traverse them at a creep. In addition, there were roadblocks at the edge of the towns, because this Friday of our journey was the beginning not only of a weekend, but of a major religious festival in honor of the destroyer/fertility god, Shiva. The police wanted to be able to take a good look at everyone entering, so the two-lane road became one-lane. (Our driver cheated and passed about twenty trucks that stood waiting in line).

Everyone was out in the best party gear: unbelievably decorated saris for the women, and young guys in well-pressed, western casual clothing. The streets are lined, mile after mile, with street vendors selling everything imaginable. There was even a ride or two: four-car miniature, wooden ferris-wheels, vividly painted and human-powered. (Two operators give each car a big push up as it passes.)

Pushkar is the site of the world’s only, place dedicated to the creator-god, Brahma. It seems he was philandering with a local girl in Pushkar, when his wife, Saraswati discovered them. Her revenge was to arrange for this place to be the only place where he would be worshipped. It is also a resort town and an attraction popular with young Europeans. For us, it was a quieter alternative to nearby Ajmer, the site of the Dargha of Moinuddin Chishti.

Our hotel was another in the “heritage” class, which means not necessarily that it is an old npoalace like the ohne at Mt. Abu. The one in Pushkar ws brand new (still bening built) but builkt to look old – crammed fullo of beautiful antique reproductions to give it a really Victorian feeling. Everything was period, down to the brass padlocks on the doors.

Sultan-ul-Hind, Hazrat Shaikh Khwaja Syed Muhammad Mu'īnuddīn Chishtī was the first sufi teacher in this part of the world. Also known as Gharīb Nawāz , Benefactor of the Poor, this contemporary of St. Francis of Assisi came from Persia at the beginning of the 12th Century, long before the Mughals. In Ajmer, he set up a soup-kitchen for the destitute. The enormous cauldrons are still visible on either side of his tomb in Ajmer.

In his solicitude for (and identification with) the poorest of the poor, he is remarkably similar to Il Poverello:

The central principles that became characteristics of the Chishtī order in India are based on his teachings and practices. They lay stress on renunciation of material goods; strict regime of self-discipline and personal prayer; participation in Sama [long meetings of prayer, singing and dancing]as a legitimate means to spiritual transformation; reliance on either cultivation or unsolicited offerings as means of basic subsistence; independence from rulers and the state, including rejection of monetary and land grants; generosity to others, particularly, through sharing of food and wealth, and tolerance and respect for religious differences.

He, in other words, interpreted religion in terms of human service and exhorted his disciples “to develop river-like generosity, sun-like affection and earth-like hospitality.” The highest form of devotion, according to him, was “to redress the misery of those in distress – to fulfill the needs of the helpless and to feed the hungry.” (

Wikipedia)His teaching of mystical Islam now has millions of followers, in several silsilas, or lines of spiritual teachers, including the Sufi Order of Hazrat Inayat Khan, and his son, Pir Vilayat. Many of our group are mureeds of Pir Vilayat. Moinuddin Chishti’s Dargha is one of the most visited shrines in India.

It sits in a large compound at the top of a low hill, reached by a broad avenue about a kilometer in length (think Hennepin Avenue from Washington to the Orpheum), from which motorized traffic is excluded.

Rahul arranged a rickshaw, so I got there pretty fast. The street and the compound were incredibly crowded. Teeming India. Although Chishti was a Muslim, hordes of Hindus visit him, too. (A holy man is a holy man!). Big security at the huge, pink gate, where shoes are left behind.

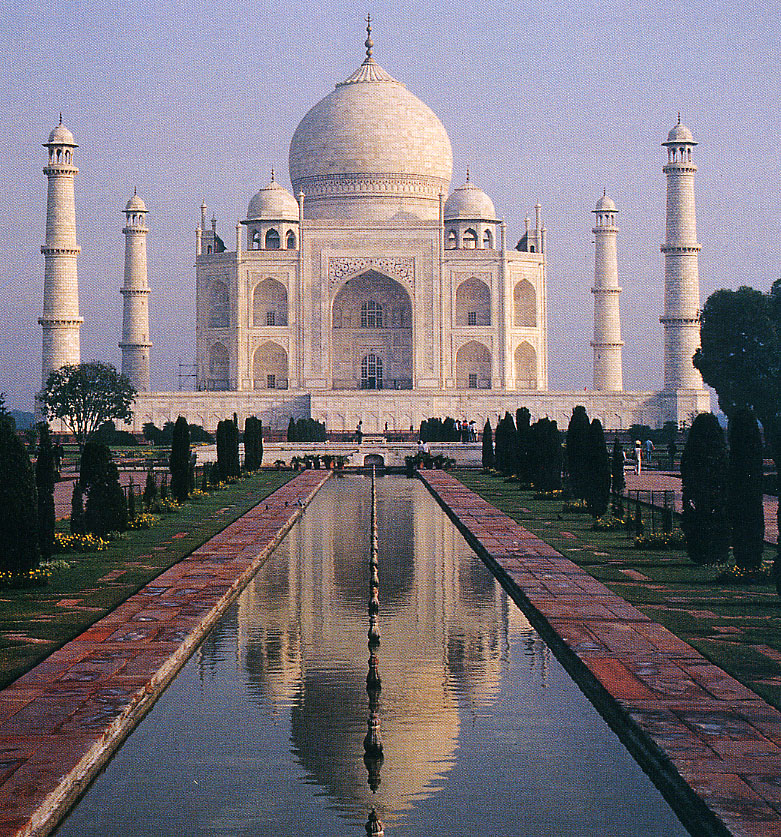

The place is a warren of marigold-vendors and shaded alcoves for instruction and study, where guys sit talking quietly. In the center is a fine mosque built by Shah Jahan (3rd Great Mogul, Taj Mahal). It stands next to the tomb, which is a square building, opened from time to time to allow pilgrims to enter and walk around the cenotaph.

It is all intiricately-carved marble and silver. (I’m pretty sure the saint would have objected. His counterpart’s tomb in Assisi is much more ascetic, even though the surrounding basilica isn’t.)

The poor love Chishti now as he loved them in his earthly life. They are everywhere, in depressing profusion. I thought I had seen misery in Mexico and Russia, but nothing can compare with this. The walk back down the avenue was a kind of journey through hell. There are hundreds of beggars, who constantly poke at prospects (and foreigners are definitely prospects). Little barefoot children poking and

pointing at their mouths, young women carrying babies, old men hobbling along beside you. And worst of all, apparent cripples and amputees rolling around on the pavement to get in front of you. (I say apparent, because some of the young cripples could also have been contortionists.) I was reminded of Slum Dog Millionaire and the horrible, deliberate mutilation of orphans to make them more pitiful beggars.

But one cannot give to all of them. And if one gives to any, all the rest come over. What is one to do, who comes to revere another who gave everything to serve the poor? They begin to seem annoying – like flies. These poor human beings, every one the image of Almighty God. It is an intolerable contradiction: open your heart to the saint, but harden it toward the beggars? This was an unforgettable lesson.

While we were still n the cool and (relatively) serene sanctuary of the Dargha complex itself we sat down in the corner of a big court outside the mosque, facing the tomb. There Sharif began the group dhikr (remembrance). All of our group chanted the word Allah. I was standing away a bit, so that I could sit on a wall and not the floor. I saw the men who had been sitting in the shade of the mosque get up and walk quickly over to see what was going on. I though they might object, but hey were just curious. Our group of Americans drew quite a crowd as we sang and danced (one at a time whirling). The Indians may been amazed, but they were not shocked.

Tomb of Moinuddin Chishti

Tomb of Moinuddin ChishtiOne of them was an old man with a white beard and a broad, toothless smile. He never stopped smiling. He was either crazy or a genuine sufi. I fantasized that he is what Shams-i-Tabriz would have looked like when he first appeared to Rumi. This old guy then accompanied our group until we finally left the compound.